by Will Katerberg

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about masculinity. I’ve been teaching some classes on the relationship between conceptions of manhood and race and American foreign policy in the late 19th and early 20th century. Think Teddy Roosevelt. I’m also thinking ahead about a course on masculinity and sports that I’m co-teaching in January with one of my colleagues, Bruce Berglund.

This morning, as they often do, the guys on ESPN radio repeatedly made the connection between masculinity, sports and war. They talked about football players going into battle. And they spoke approvingly of men who, on the field and in their personal lives, “take care of business” and “do things the right way.”

One of the issues they’ve wrestled with regularly in the past half year has been problems with domestic violence by football players, recently by stars like Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson. These are men whose “savage” vigor is admired on the field, much like with soldiers, but whose seeming inability to restrain it off the field is a publicity nightmare for their teams and the NFL.

The guys on ESPN have also wrestled with the problem of injuries on the field, notably concussions. Can the NFL protect the health of players without domesticating the game, such that it no longer requires or fosters the manhood associated with violent sports like football? Should it even try? Or should players be allowed to decide for themselves, as men, whether the risks are worth it?

During the heyday of Teddy Roosevelt, in the 1890s and 1900s, anxiety about manhood was common in the United States (and in Canada, Great Britain, and western Europe). The challenges of harsh environments and hard work on America’s rural frontiers had once made American men morally and physically vigorous, popular intellectuals like Roosevelt believed. The prospect of fighting “savage” Indians, and even more the occasional reality, had tested and honed the mettle of American men. Now that America was becoming urban and industrialized, would American men lose their vigor and become “soft” and “over-civilized”?

Concerns about race exaggerated these anxieties. What would immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe and Asia do to American “bloodlines,” especially now that there was no frontier to transform foreigners into vigorous Americans? “Old stock” Americans like Roosevelt, with their roots in the Protestant countries of Western and northern Europe, were having fewer children. Some Americans talked about “race suicide.”

In this context intellectuals and politicians like Roosevelt advocated substitutes for the frontier and the kind of labor farmers once did, as a way of transforming immigrants into Americans and more generally ensuring the vigor of American boys and men. Calisthenics and sports in school to encourage physical fitness. Organizations like the Boy Scouts to teach boys woodcraft, hunting and martial skills, and the moral and physical vitality that came with them. Theologians talked about “muscular Christianity,” idealizing not the meek and mild Jesus they associated with womanly Christianity, but the vigorous Savior who took a whip to the money changers and cleansed the temple of their corruption.

Roosevelt also saw war for empire as a way of continuing what the frontier had once offered, in fighting against and defeating over-civilized Europeans like the Spanish in the Spanish-American war of 1898 to 1899, and in fighting Filipinos to secure and colonize America’s new “Gateway to China.” Those who opposed these wars and the creation of an overseas American empire were “soft,” not manly.

Roosevelt self-consciously tried to embody these ideals of masculinity, and he and his supporters played them up in his campaigns for office as a politician, notably in his vice presidential campaign in 1900 and his presidential campaign in 1904. Roosevelt did not just write histories of the American frontier; he owned a ranch in the Dakotas and worked it as a cowboy, hunted buffalo, and even joined the occasional posse to find outlaws (whose rough vigor he admired, even if he lamented their lack of enough civilization to restrain that vigor and use it for good ends).

Roosevelt self-consciously tried to embody these ideals of masculinity, and he and his supporters played them up in his campaigns for office as a politician, notably in his vice presidential campaign in 1900 and his presidential campaign in 1904. Roosevelt did not just write histories of the American frontier; he owned a ranch in the Dakotas and worked it as a cowboy, hunted buffalo, and even joined the occasional posse to find outlaws (whose rough vigor he admired, even if he lamented their lack of enough civilization to restrain that vigor and use it for good ends).

In 1898, at the start of the Spanish-American war, Roosevelt organized a militia unit known as the Rough Riders, made up of some of his friends from Yale, who like him were obsessed with masculinity, and frontiersmen he’d gotten to know during his time in the American West. Though he had been a sickly, asthmatic boy, he became a vigorous man.

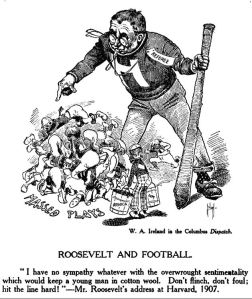

Depictions of Roosevelt campaigning for office and later as president invariably touted or mocked the ideals and persona that he cultivated, depicting him as a boxer, a cowboy, a Rough Rider, a hunter, and more.

Depictions of Roosevelt campaigning for office and later as president invariably touted or mocked the ideals and persona that he cultivated, depicting him as a boxer, a cowboy, a Rough Rider, a hunter, and more.

But this same Teddy Roosevelt is also the man who won a Nobel Peace Prize, for negotiating an end to a war between Russia and Japan, and the man who saved football. In the same year in fact, 1905.

Roosevelt approved of violent sports, saying: “I believe in outdoor games, and I do not mind in the least that they are rough games, or that those who take part in them are occasionally injured.” Like many other Americans he was concerned about the number of deaths and injuries in football during the early 20th century—18 deaths in 1905 alone. But he also feared that college presidents might “emasculate” the game in trying to reform it. Some universities had suspended their football programs. So Roosevelt summoned coaches from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to the White House to save the game (from itself).

Roosevelt approved of violent sports, saying: “I believe in outdoor games, and I do not mind in the least that they are rough games, or that those who take part in them are occasionally injured.” Like many other Americans he was concerned about the number of deaths and injuries in football during the early 20th century—18 deaths in 1905 alone. But he also feared that college presidents might “emasculate” the game in trying to reform it. Some universities had suspended their football programs. So Roosevelt summoned coaches from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to the White House to save the game (from itself).

Roosevelt should not get all of the credit for reducing the level of brutality in football and changing how the game was played. But he used his “bully pulpit” to good effect.

One hundred and ten years later not much seems to have changed. Or at least not as much as one might think—given decades of changes values associated with feminism, Title IX, gay rights, and the like, and their impact even on sports. President Obama hosted a White House summit on sports concussions in May of this year. Concerned observers once again wonder whether the game can be saved without emasculating it. And sports and war continue to provide metaphors for each other. It is “not a dead but a living relationship.”

—

William Katerberg’s areas of focus are the history of ideas, the North American West, environmental history, and world history. He is the chairperson of the History Department at Calvin College.

Thanks for the remarks, Professor Katerberg. I enjoyed the great connections between the social history of America and the problems of the present.

We’ll be getting to the Spanish-American War soon in my US History class, and excerpts from this may end up in my course: many of my students play football over here at Holland Christian, so bringing up issues of muscular Christianity in history are excellent ways of connecting current events and activities with our nation’s past. Plus, it’s TR, and you know I have a special place in my heart for him.

LikeLike