Eric M. Washington

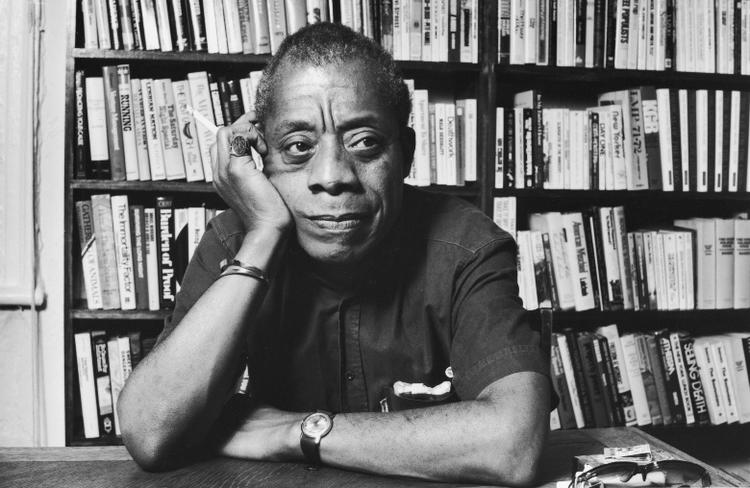

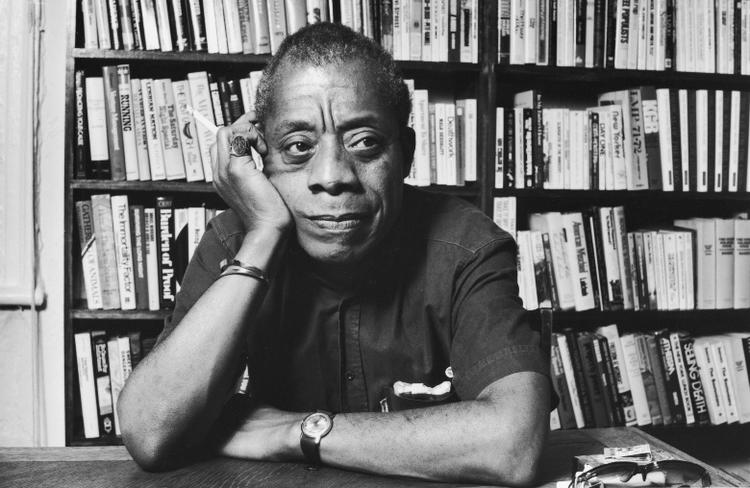

On August 2, 2024 the world will celebrate and commemorate the 100th year of James Baldwin’s birth. During this year I have dedicated myself to reading a portion of James Baldwin’s writings each day. Other than familiarizing myself much more with the work of Baldwin, I have decided to embark upon this journey to listen, to learn, and to follow this ancestral prophet. In being an intellectual acolyte of Baldwin, I intend “to tell as much of the truth as one can bear, and then a little more.”[1] This is what I’m referring to as the Baldwin Paradigm. This should be the intention of every African American historian in the classroom. We must be truth-tellers.

James Baldwin came into my intellectual orbit during high school. In my senior year of 1985-1986 my English teacher taught us from the anthology Black Voices originally published in 1968. This classic anthology of African American literature is full of poetry, prose, short stories, and non-fiction by a panoply of great 20th-century African American writers including James Baldwin. Because Baldwin was very much alive when the anthology became extant, there were two of his writings in the book, “Autobiographical Notes,” and “Many Thousands Gone,” which are from his collection of essays Notes of a Native Son (1955). There is also a compilation of some of Baldwin’s interviews and remarks by the poet Dan Georgakas. Though I had a book in my hands that contained three texts of Baldwin’s, my teacher failed to assign any of those writings. But I had viewed the film adaptation of Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain in 1985 during my junior year. Watching that film was my true introduction to Baldwin.

In my course work at Loyola University-New Orleans as a Sociology major and Afro-American history minor, none of my professors assigned me any readings by Baldwin though he had died during my sophomore year. There were references made to him in a course or two, but I read nothing by him. That changed when I graduated in 1990. I had a habit of reading outside the curriculum all through college so when I graduated I decided to fill in some of the gaps in education. I chose to read Baldwin’s 1962 novel, Another Country in early 1991. Reading that book as my initiation into the Baldwin literary canon was a baptism by fire. It challenged my notions of race, gender, and sexuality; and it’s been a book I’ve gone back to periodically over the past 30 plus years. That was basically it for me and reading Baldwin until 2016.

In the fall semester of 2016 I began to teach an interdisciplinary course called “Black Lives Matter” in light of the new movement that had stirred up so much new activism and controversy. I crafted the course as one in what I termed the Black Humanities arguing that African American writers have asserted their worth since the 18th century. One of the books I assigned was Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. I had read the book for the first time earlier that year, and knew that Baldwin’s arguments and assertions forwarded in 1963 was germane in the racial climate of 2016.

Also in 2016, Raoul Peck released his documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Peck based the documentary on Baldwin’s incomplete book project on Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr begun in 1979. He never finished it. He never got past a 30-odd page introduction. In the documentary, Peck pulled together snippets from Baldwin’s essays and interviews and crafted a wonderful narrative that spoke directly to that contemporary audience. In the fall of 2017, I showed the aforementioned documentary I Am Not Your Negro in “Black Lives Matter,” and we read the companion book. I screened the documentary and taught the book until the course ended in the Spring of 2021.

This past fall semester, I team taught another interdisciplinary course, “Race in America” with my wife and Social Work professor, Sherita M. Washington. We decided to teach a Baldwin essay published in 1985 titled “On Whiteness…and other Lies.” I had taught the course since 2021 and had used a variety of African American primary sources, but not Baldwin. After teaching this essay, I am convinced even more of Baldwin’s central place in African American literature and African American Studies.

As I have taught Baldwin in courses centered on race for the past seven years, I never believed it necessary for me to teach Baldwin in African American history. This will change this semester. It’s time to introduce my history students to Baldwin in this 100th year of his birth. Beyond this, Baldwin is an important African American historical figure whose writings need exposure across the humanities curricula. Because of these two factors among many, I have assigned The Fire Next Time this semester in African American history. I love this text, and I believe students will gain a different perspective on the Civil Rights Era by reading, discussing, and writing about it.

It’s Baldwin’s relentless truth-telling that makes him essential reading for this time. And it makes him essential for the African American history curriculum. From its inception as a discipline, African American history aims to be a corrective to the dominant narrative of American history. Few writers I know called upon Americans to free themselves from the myth of the American past, especially as it pertained to the treatment of persons of African descent. Baldwin once said, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals.”[2] Truth.

[1] James Baldwin, “As Much Truth As One Can Bear,” in The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings, ed. Randall Kenan (New York: Vintage International, 2010), 35.

[2] James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro (New York: Vintage, 2017), 107.

Eric Michael Washington is professor of history and director of Africana Studies at Calvin University. He is primarily interested in studying the African American church from its development in the late 18th century through the 19th century, and individual Christians, primarily Calvinists. He also has a growing academic interest in the growing “Black and Reformed” movement in North America