by Jenna Hunt.

My Museum Studies masters’ thesis focused on museums of communism, and as part of my research I traveled to Central and Eastern Europe and analyzed several museums as case studies. One of these was the Perm-36 Gulag Museum, located on the western edge of the Ural Mountains. I arrived in the city of Perm, Russia, in May 2008, and my hired guide took me on a two hour drive through the remote countryside to the museum. Perm-36, which opened as a museum in 1996, the only one in Russia built on the site of a former gulag camp. Other camps, flimsy to begin with, quickly faded into the tundra, but the Perm-36 camp was carefully restored into a memorial museum. Much of reconstruction work was done by former prisoners and their families, a poignant example of how a museum can work with members of an oppressed community to tell their own history.

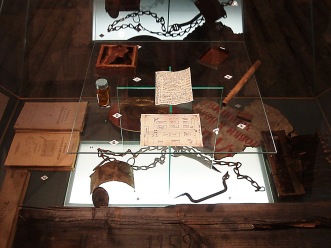

Perm-36 was by far my favorite among the four museums that I studied for my project. A museum guide led me through the various buildings – the barracks, the isolation cells, the workshop – and thoughtful displays provided a nuanced history of the dissidents who had been imprisoned at Perm-36, the gulag system of prison camps, and the broader story of oppression and atrocities committed under the Soviet government. Years later, I still remember the impact of seeing handwritten notes and maps scribbled down by some prisoner and hidden in the walls. Seeing human artifacts like these brings history to life for me in a way textbooks cannot. And through a series of travelling exhibitions, the museum was able to reach a wider audience, including exhibits in the US co-sponsored by the Smithsonian.

So, imagine my surprise to discover that this same museum – a place where the local community could engage with their traumatic history, and where knowledge about that history could be spread to wider audiences – has been shut down and reimagined into a propaganda tool for Putin’s Russia.

In March 2015, the museum was forced to shut down after a three-year struggle with the government that began shortly after Putin was re-elected for his third term as president. The museum had been in the running for UNESCO World Heritage Site designation, but the Russian government withdrew its support. Over the next few years, the museum was subjected to a series of inspections, financial investigations, and public attacks. It was accused of promoting fascism and dissidence against Russian government, using language eerily similar to the charges once faced by Perm-36’s prisoners. In June 2014, Russian state television aired a documentary claiming that the aim of the museum was “to teach children that Ukrainian fascists are not as bad a history textbooks portray them, whilst their grandchildren cause genocide in eastern Ukraine.” The date here is significant, coming just a few months after Russia’s controversial invasion of the Crimea. The same year, the director of the museum was fired, and she and her colleagues were denounced as “subversives,” and the following March it was forced to shut down entirely.

The Russian government reopened the museum a few months later, in the summer of 2015. Putin’s bureaucrats exercise tight control, with the new management team promising a more “objective” view of history. Before the government takeover, the official name of the museum was the “Memorial Historical Center of Political Repression Perm-36.” Its new name is less provocative: “The Museum of the History of Camps and Workers of the Gulag.” The new version of the museum is about the camp system in general rather than the suffering of political prisoners under the Soviet regime. Some of the original exhibitions remain, but others, such as an exhibition on the high-profile political prisoners, were deemed “too controversial.” The new displays emphasize things such as the camp’s timber production and its contribution to victory by the Soviets in World War II. In an ironic twist, the museum’s new management includes former prison guards, rather than the former prisoners who ran the previous iteration.

The Perm-36 Gulag Museum is not the only site that is experiencing this kind of revisionist history. The Solovetsky Islands, site of the infamous Solovki prison camp, has also been home to a monastery since the 1400s. The Russian Orthodox Church has recently begun restoration efforts on the monastery that some see as an effort to erase signs of the prison camps there. In 2011, the Ministry of Culture replaced an unofficial exhibition at the monastery with a small museum in a nearby village. The original exhibition’s creator accuses the new official museum of failing to portray the harsh realities of gulag life.

Despite these events to “disappear” museums and other memorial sites, official policy in Russia seems to be shifting toward commemoration rather than erasing gulag history. In August 2015, Prime Minister Dimitry Medvedev signed the “State Policy on Commemorating the Memory of the Victims of Political Repression.” The policy, developed at the order of Putin and the Human Rights Council, states:

Russia cannot fully become a state where there is the rule of law and occupy a leading role in the world community without immortalizing the memory of many millions of our people who were the victims of mass repressions.

The policy calls for archives to be opened, museums created, and databases of victims compiled by 2017 – just in time for the centenary of the Russian Revolution, and the 80th anniversary of the peak of the Terror in 1937. A few steps have been taken in that direction. Just a few weeks ago, the first full-fledged gulag museum sponsored by the Russian government opened in Moscow in its new, much larger building. The opening coincided with a national day of remembrance for Stalin’s victims. And after a public competition, a design was recently chosen for monument to the gulag victims, which should be unveiled in Moscow in October 2016.

This official policy is a step in the right direction, but activists express misgivings and have raised a number of concerns: there was no legal weight to Medvedev’s statement; it was not signed by Vladimir Putin; and it seems to contradict what is actually happening on the ground, where former gulag sites and memorials are disappearing rather than receiving government support.

Paradoxically, monuments to Josef Stalin are also going up all over Russia, and Putin is reviving Stalinist symbols and practices, particularly ultra-patriotic and militaristic programs and displays. A poll earlier this year in Russia revealed that more than half of the population has a favorable view of Stalin, despite the fact that millions suffered imprisonment and death as a direct result of Stalin’s policies.

I’ll conclude with the words of Vladimir Ryzhkov, a former State Duma deputy, writing for Moscow Times:

It is absurd to erect monuments to the victims of repression while simultaneously raising monuments to the very person responsible for their death. That is not a sign of reconciliation and tolerance, but an open manifestation of deeply conflicting values. It reflects the deep split in modern Russian society, the mixing of absolutely incompatible things and a fundamental failure to distinguish between good and evil.

—

This post was originally written as an assignment for Professor Berglund’s HIST 372, Modern Empires: Russia & China, Fall 2015.

Jenna Hunt is administrative assistant for the Calvin history department and program coordinator for Seminars at Calvin. A Calvin history alum (’07), she earned an MA Museum Studies and has worked in several museums in the US and UK. When she’s not in the office, she’s probably watching Star Wars or reading about Russian history with a cat on her lap.